Iran’s nuclear ambitions have long been a headache for the Middle East and beyond. Trump’s maximum pressure approach to an increasingly conservative, hostile Iranian government has not solved the nuclear problem for the Biden administration. Ongoing sanctions are expensive and difficult to monitor. There is increasing pressure from both inside and outside Iran to return to the more user-friendly 2015 agreement brokered by the Obama administration. A panel of experts from the US, Israel, the UAE and the EU gathered recently at a wide-ranging conference on the Middle East, organised by the Brookings institute. In spite of America’s desire to focus elsewhere, all agree that Iran’s nuclear programme is a security threat that simply cannot be ignored.

Iran began its nuclear development programme in the 1950’s under the Shah. However, it was only in the 1980s and 90s that the Islamic Republic began taking a renewed interest in it. Since then, various initiatives designed to limit Iran’s nuclear ambitions have been taken. Most significantly perhaps was the 2015, Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement brokered by the Obama administration with Iran. Designed to monitor the Iranian nuclear programme, it had the backing of the UN Security Council members, Germany and the European Union.

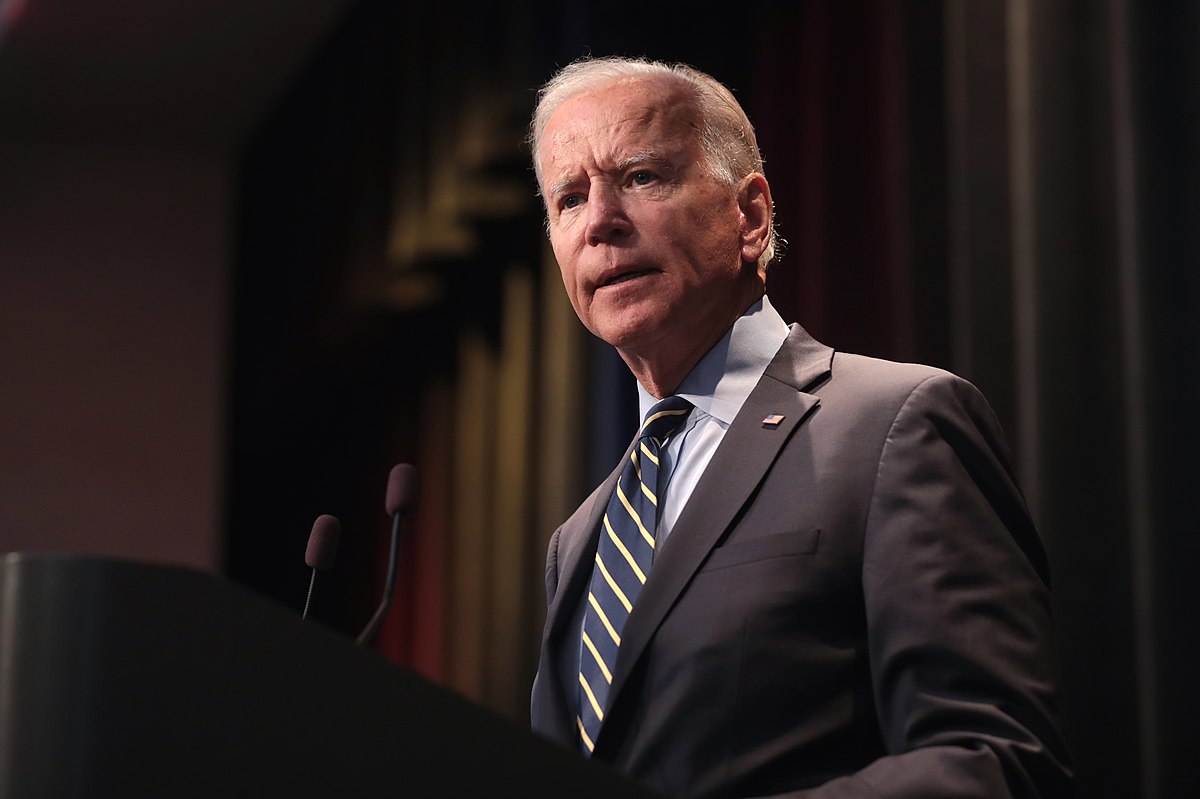

‘Have we done maximum pressure long enough? ‘– Suzanne Maloney

Others, including Israel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia argued that it was not strong enough. They claimed that Iran simply used the agreement to buy time in order to further develop their uranium enrichment programme under the cover of a compliance that was difficult to monitor. The Trump administration ceased to follow the agreement. Instead, it took what it called a ‘maximum pressure’ approach to Iran’s nuclear ambitions. This involved more extensive sanctions and a zero tolerance approach to its nuclear development programme. Did this approach work? ‘Realistically, we are never going to come to a clear conclusion on that one’ admits Maloney.

As an increasingly fractured, poverty-stricken Iran approaches national elections in June. The Biden administration is under pressure to make clear its own approach to what most agree is the most dangerous country in the Middle East. ‘This is not a static situation’ says Suzanne Maloney, Vice President and Director of Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institute. The Iranians are actively taking steps to force the US and international community, to act as quickly as possible, in order to gain a strategic advantage, explains Maloney. Amos Yadlin, Former Head of Military Intelligence Directorate – Israeli Defense Forces, explains that Israel is concerned about this sense of urgency. ‘Don’t rush because the Iranians are pushing you’ says Yadlin. ‘The Iranians want to go back to the 2015 JCPOA more than you, because it serves them!’

EU keen to return to the 2015 Nuclear agreement with Iran – Ellie Geranmayeh

Ebtesam Al-Ketbi, President of Emirates Policy Center, agrees with Israel. ‘We are not against diplomacy’ she explains, ‘but it should be played well.’ She expresses concern about what she sees as the naivety of the American and European approach. ‘You have to understand how the game is being played in Iran’ she says and advises ‘strategic patience’ on the part of the Biden administration. Such attitudes stand in clear contrast to those of Ellie Geranmayeh, Deputy Director of the Middle East and North Africa Programme – European Council on Foreign Relations. While acknowledging that the EU, like the US, sees Iran’s nuclear ambitions as the number one security threat for both sides of the Atlantic, she explains that Europe is keen to get back to the 2015 deal as soon as possible.

The EU views Trump’s maximum pressure approach as largely unsuccessful with regards to restraining Iran’s nuclear ambitions including the develop of its nuclear enrichment programme. With an increasingly conservative political elite in Iran threatening to oust the comparatively moderate incumbent President, Rouhani, in the upcoming elections, the EU feels it is a ‘now or never’ moment to get Iran back to the negotiating table. Geranmayeh points to the legal mandate from the UN Security Council for a return to the JCPOA and the positive role of personal diplomacy between Biden and Rouhani. The longer this current state of limbo continues with Iran waiting for some sort of economic relief from the West, the greater the chance of increasing Iranian aggression and further development of their nuclear programme, Geranmayeh argues.

‘We have to be very clear-eyed about the nature of Iranian leadership’ – Suzanne Maloney

Maloney argues that one ‘can’t have things good, fast and cheap, you have to pick.’ With regards to Iran, she believes that the US approach should be good rather than fast. She is reluctant to be pressured by the political timeline presented by the Iranian national elections in June and points out that although Rouhani is currently in power, Iran’s nuclear programme has always been subject to consensus decision making including the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. She describes as ‘absurd’, the idea that the US has any influence over Iranian domestic politics.

With these in mind, she maintains that the US’s central objective has to be the deterrence of Iranian nuclear capabilities. ‘We have to be very clear-eyed about the nature of Iranian leadership’, she warns. Hostage taking and support of proxy attacks in Iraq and other Middle Eastern countries are all examples of what Maloney sees as political brinkmanship on the part of Iran. ‘I don’t think we have forever and a day to deal with the Iranian problem, but I also don’t think we should let the Iranians try and force a deal on the rest of the world that is sub-optimal’.

Wherein lies a solution?

Yadlin speaks of the importance of having what he terms a ‘Plan B’. ‘This is necessary, when you’re dealing with a country like Iran’, he maintains, pointing out that Iranian leadership is not curtailed by democratic election cycles. ‘The Iranians plan for half a century ahead’. He argues that in order for diplomatic pressure to work, it must be backed by a credible military option from both the US and Israel. ‘When sanctions were really painful, the Iranians came to negotiate. Unfortunately they were much better negotiators than the other side.’ However he agrees that broadening the JCOAP agreement is unrealistic because of the complexity of the task. Instead he suggests a two prong approach: one part involves diplomacy leading to a possible nuclear deal. The other involves Israel and the US continuing to work together to curtail Iran’s military activity in the Middle East.

‘You have to understand the region otherwise Iran will literally take you hostage’ – Ebtesam Al-Ketbi

Ebtesam Al-Ketbi agrees that ‘the Israeli’s understand the strategic approach of the Iranians far better than the Europeans and the Americans’. She explains that for the Gulf States the threat of ballistic missiles from Iran is of greater concern than a nuclear attack, because of their geographical proximity. For this reason, they did not support the 2015 nuclear agreement and are in agreement with Israel’s two part approach. ‘You have to understand the region otherwise Iran will literally take you hostage’ she warns. Al-Ketbi also expresses concern that if the US significantly downgrades its involvement in the Middle East, the Russians and the Chinese will ‘come in through the window’.

Geranmayeh agrees that a parallel track with regard to Iran and other regional issues is part of the European position. However she does not believe that an Iranian presence across various Middle Eastern ‘hotspots’ can simply be removed. Instead, Europe would like to see the UN overseeing a dialogue process between Iran and its Gulf Cooperation Council neighbours. She points out too that in order to sit down and negotiate with Iran, the US will also need to be prepared to make some concessions.

For Maloney, the problem is largely structural. She notes that the politics of the Iranian establishment has ‘narrowed significantly in the past decades and this has not been primarily the result of US policy.’ She suggests instead that the structure of power in Iran is set up in such a way as to prevent a more wholesale shift toward greater democracy. The Supreme Leader does not want the expansion of the political rights that are guaranteed in the Iranian constitution but have never been adhered to. The military agrees with this position. As a result, ‘there is no opportunity for anyone who has a different perspective, to advance in Iranian politics’, Maloney explains. She admits to becoming ‘more jaundiced’ in her views on Iran over the years and warns that ‘this is a very, very dangerous government’ with whom one needs to negotiate very carefully.