Just a five minute walk from where I Iive, you can find the Levenseindekliniek or End of Life clinic. It is a well maintained if unassuming brick house, tucked away on a quiet street in the Hague. The Netherlands was the first country to legalise euthanasia in 2002. As populations in developed countries age and the right to choose becomes ever more widely accepted, requests for euthanasia are increasing. But it also raises important questions about the value of life for its own sake and how much suffering society is willing to sanction.

The law in the Netherlands allows for GPs to assist patients with euthanasia under certain specified conditions. However, a number of GPs do not feel capable or comfortable with this responsibility. Thus there is a gap between what the law allows and the reality for those looking to choose when they die. This is where the Levenseinde clinic comes in, explains Annerieke Dekker, who works for the clinic. ‘It is not actually a clinic. It is more of an office, as most people prefer to die at home,’ she continues.

Inside, it is quiet and tastefully furnished. Annerieke tells me that the clinic was started six and a half years ago by the Right to Die Society. Initially funded largely by donors, it is now almost entirely funded by the Dutch health insurance system. The clinic’s long term goal is to provide training and support for GPs around the country so that they will feel empowered to take responsibility for euthanasia requests from their patients. However at present it is still common for consultants attached to the clinic to assist GPs with such cases. They also provide training for GPs who are unfamiliar with euthanasia law.

How does it work?

A patient can make a request for euthanasia through his/her GP or approach the clinic directly. However, the clinic will always contact the patient’s GP to discuss the issue and request access to medical files. If the GP is unwilling to get involved, the clinic will then appoint a two person team, consisting of a doctor and a nurse. They will investigate the case together and are usually located in the area where the patient lives. If the case is straight forward, for example, s/he is suffering from terminal cancer and is in a lot of pain, a decision can be made fairly quickly.

However if it concerns a patient with a psychiatric condition then the process can take longer, Annerieke explains. In all cases, an independent opinion from another doctor is also requested. However in the case of a psychiatric patient, the independent opinion of a psychiatrist is also required. Once the decision is made, the case is discussed once more at the Levenseinde clinic in order to consider any anomalies or complications that might arise. Euthanasia is then performed by the doctor from the original doctor/nurse team.

When does suffering become ‘unbearable’?

The Levenseinde clinic was involved in the recent case of Aurelia Brouwers, a 29 year old Dutch woman who had been suffering from a variety of psychiatric illnesses for many years. She was helped to die in January this year at her family home in Deventer, the Netherlands. This was after being declared eligible for euthanasia under the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act (2002). This law permits the ending of lives where there is ‘unbearable suffering’ without hope of relief. Although Brouwers did not have a terminal disease, she suffered from anxiety, depression and psychosis and had attempted suicide numerous times. An inpatient at a psychiatric hospital for nearly 3 years, she had also served time in prison for arson.

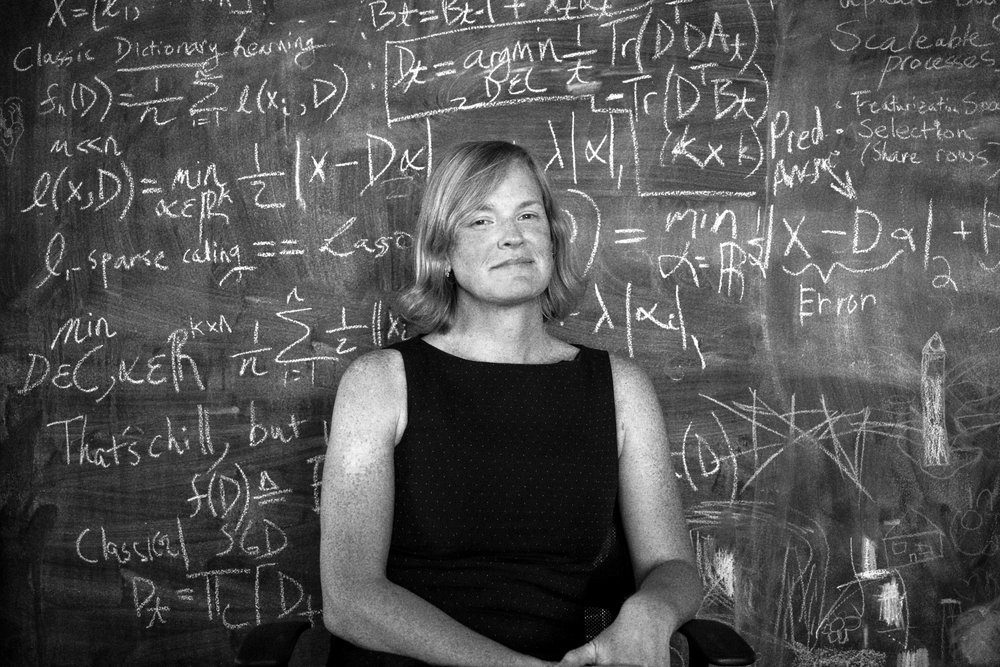

Her case sparked heated debate as it raises the question of what exactly constitutes unbearable and hopeless suffering. Many people suffering from dementia present a moral dilemma for doctors. GPs find it very difficult to euthanize patients who are unable to give verbal consent even if they have signed a declaration of wishes in advance. Yet many who see their parents or grandparents in the grip of advanced dementia wish to opt out of such a bleak end-of-life scenario when their time comes. Indeed, research by end-of-life expert at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, Professor Agnes van der Heide, suggests that public opinion in the Netherlands shows substantial support for further liberation of euthanasia laws, especially with regards to dementia.

People want to choose how, when and where they die.

There have been proposals by Dutch politicians like Pia Dijkstra, a member of centrist-liberal party, D66, to allow anyone over 75 without a diagnosis of physical or mental illness, to request euthanasia. While two years ago, the Netherlands’ health and justice ministers issued a joint proposal for a ‘completed life’ pill. This would give anyone over 70 years of age the right to receive life-ending drugs, without involvement of a doctor. The proposal was voted down in parliament but it highlights a key issue for any country contemplating euthanasia legislation. How and to what degree will it inevitably expand?

Annerieke Dekker tells me that the Levenseinde clinic does not support the extension of current euthanasia laws. They find they can do their work perfectly well within the current legal framework. However, history suggests that the prospect of increased control over our lives and destinies is difficult to resist. MPs like Dijkstra claim that a growing number of older people in the Netherlands want to decide for themselves how, when and where their life will end. For many this constitutes dignity, for others it represents a lack of respect for the value of life itself. In a country like the Netherlands, where death by euthanasia is at 4% and rising, traditional ideas about death are clearly changing. For better or for worse, many agree that the process is irreversible.