As the world continues to struggle with the corona pandemic, progress may seem painfully slow. But as Steven Pinker recently pointed out in an online discussion organised by De Balie in Amsterdam, ‘Data shows that progress is a real phenomenon’. The Harvard-based psychologist reiterates the argument he makes in his best-selling book, ‘Enlightenment Now’: apply reason, science and humanism to the problems of the world and the result is progress. Yet, in spite of large amounts of data provided in support of world progress, many believe humankind is in a terrible state.

‘It’s not a case of seeing the world through rose coloured spectacles’ insists Pinker. ‘The case I’m making is really one of data’. The psychologist cites life expectancy, which has gone from an average of 31 years of age for most of history to 71 years of age globally and 80 years of age in developed countries. Two hundred years ago 90% of the world lived in extreme poverty, this figure has now dropped to 9%. Suicide worldwide has fallen by 40% in the last 30 years. War used to be the norm, we are now living in what some have called, the long peace. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t room for more progress, Pinker explains. Neither does it mean that progress is inevitable. But a lot of good news, ‘consists of nothing happening’. Bad news is usually far more sudden and dramatic. It is also therefore easier to report. So, unless you look at the data, your view of the world can be out of sync with reality.

Nevertheless, ‘a lot of forces in the universe are out to get us’ Pinker warns. The most prominent of these is disease. Infectious disease has been the norm throughout history. Wars kill far fewer people than pathogens. ‘The bugs are out to kill us and we’re out to defend ourselves’, says Pinker. So it is inevitable that Covid 19 is going to set back progress. Life expectancy will go down and poverty will increase. But, reason, science and humanism have been developed to help us fight disease, Pinker insists. And Covid is no different. Although daily news headlines might decry the spread of corona and the rising death toll worldwide, Pinker points out that in comparison to previous pandemics, our progress in dealing with Covid 19 has been remarkably speedy.

‘We should invest in the equivalent of a fire department for pandemics’ – Steven Pinker

Pinker points out that we identified the pathogen within days. It took 3000 years to identify the pathogens associated with smallpox and polio. 15 years for HIV and 5 years for Ebola. Within weeks, the DNA structure of the corona virus was established and a vaccine is months away. However this does not mean that scientists and/or politicians have all the answers. Neither should we expect them to. Indeed, the psychologist suggests that we should treat pandemics the way we treat fires in cities. We should invest in the equivalent of a fire department for pandemics which will be at the ready for when a pandemic emerges. One of the biggest psychological obstacles to the fight against this pandemic, he argues, has been its politicization, from an early stage.

Politics and the media focus largely on the short term. ‘If you look at the news, things never get better. It’s only the data that shows the progress we have made.’ But Pinker agrees that in terms of the environment, progress is less evident. The climate crisis is much more sever than Covid. The issue is energy. Every aspect of life needs energy. Thus far we have depended largely on fossil fuels for our energy needs. ‘Burning fossil fuels has solved many problems but has also created many problems’.

‘We should be aiming for a clean-enough environment’ – Steven Pinker.

Pinker believes that the problem is solvable but ‘we’re going to have to do the math and realise that energy is good.’ Particularly in developing countries like India and China. ‘They’re going to want to get rich and we should not stop them.’ As with all things, Pinker, sees the climate crisis as a trade-off. If we want a perfectly clean environment we would all be living in poverty, he maintains. ‘We should be aiming for a clean-enough environment’. And indeed, in developed countries, the data shows that water and air have become significantly cleaner over time.

Principal research scientist at MIT, and author of More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources—and What Happens Next, Andrew MacAfee argues that degrowth is not necessarily a prerequisite for saving our planet. Over the last fifty years, the world’s richest countries have learned how to reduce their footprint on Earth. MacAfee claims that the data shows a decoupling of growth and environmental harm in wealthier countries.

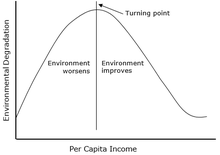

Rich countries have reduced their air pollution, for example, not by embracing degrowth or offshoring, but by enacting and enforcing smart regulation. Research from a 2018 study shows that in the US, changes in environmental regulation rather than in productivity and trade account for most of the emissions reductions. China too, has succeeded in significantly decreasing air pollution in densely populated areas (30% reduction between 2013 and 2017) thanks to government policy. MacAfee points to the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) by way of explanation. Named after economist Simon Kuznets, the curve posits a relationship between a country’s affluence and the condition of its environment.‘

So why the reluctance to embrace the progress that centuries of dedication to science, reason and humanism are able to offer us? Perhaps a natural human tendency toward focusing on the negative. An evolutionary quirk designed to keep us every ready to face danger in whatever shape or form it might come? Perhaps the never ending stream of negative news reporting that most of us accept almost unquestioningly.

Perhaps, as MacAfee suggests, there are some for whom their jobs and reputations depend on continued adherence to the degrowth argument in spite of evidence to the contrary. But surely the ultimate question is how many of us would be willing to accept recession if it weren’t necessary. MacAfee’s ecomodernist argument posits that most of the world’s people would much rather, ‘eagerly sign up to climb our new green path to prosperity’. Progress is not inevitable as Pinker repeatedly points out. But neither should we reject it on grounds of fear, negativity or ignorance of the data.