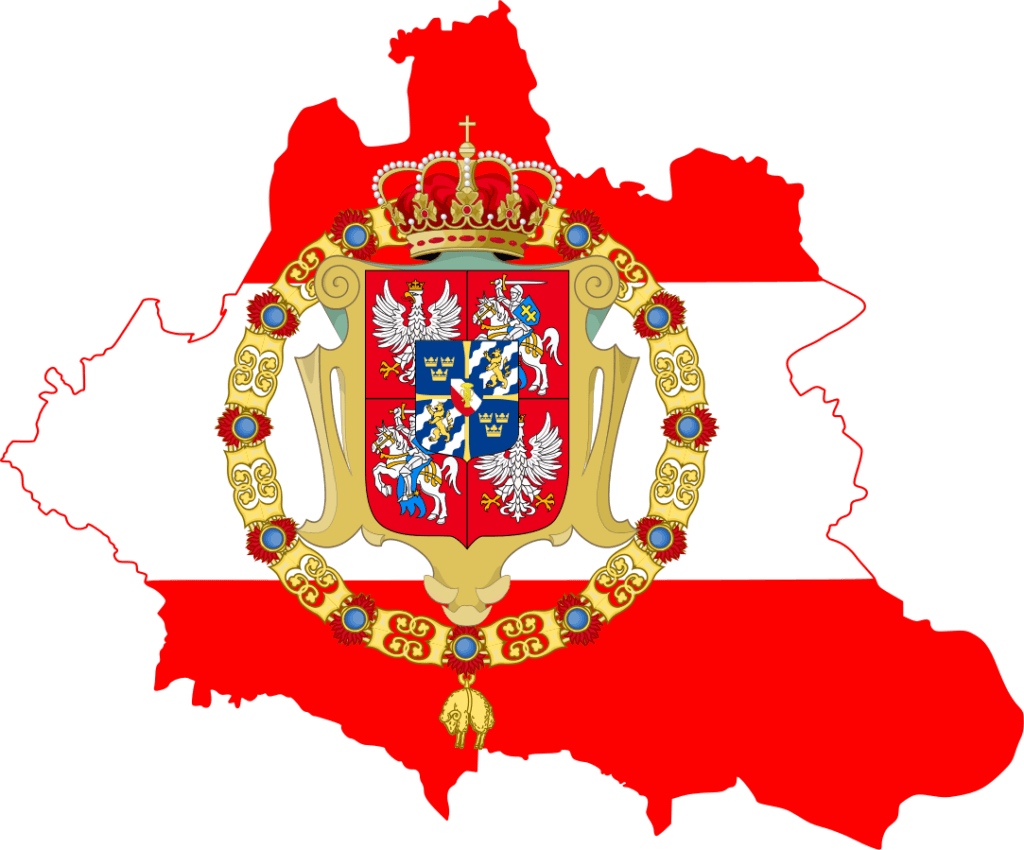

Yesterday, the Nobel Prize for Literature (2018) was awarded to Polish writer, Olga Tokarczuk . I attended a celebration at the Polish Embassy in the Hague marking the 450th anniversary of the Union of Lublin. Some call it the precursor to the European Union. On Sunday, national elections take place in Poland where right wing, Law and Order party is expected to win another term in office. As one of the largest countries in Europe with some of the most dramatic history, Poland’s future and past merit attention.

Lublin is the largest city in eastern Poland, it sits near the border with Ukraine and Belarus. In 1569, it became the site at which two sovereign countries – the Kingdom of Poland and the Duchy of Lithuania merged to form a Commonwealth. The two nations agreed to be ruled by a single monarch, elected jointly by both nations in free elections. Like the European Union of today, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had one currency and conducted foreign affairs and defense policy jointly. However, government departments specific to each country were preserved as were their official languages, armies, treasuries and judicial systems.

At its zenith, in the early 17th century, this dual state covered almost 1 million square kilometers and sustained a multi-ethnic population of 11 million people. Indeed the Commonwealth was marked by relatively high levels of religious tolerance, guaranteed by the Warsaw Confederation Act of 1573. Although Catholicism was the dominant religion of the state, freedom of religion for other faiths including Islam and Judaism was granted.

Celebrating and problematizing diversity.

Perhaps it is not so surprising that Nobel Prize winner, Olga Tokarczuk’s most recent novel, The Books of Jacob is set in the early years of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Described by its English translator, Jennifer Croft, as a rewriting of history designed to ‘celebrate and problematize diversity of faith, gender, language and nation’, the book follows the life of Jacob Frank. He is a Jew of Sephardic origins who was born in Poland but grew up in Romania and the Ottoman Empire. In the summer of 1579, he led the conversion of thousands of Jews to Catholicism in what is now the Ukraine. Seeking to establish himself as the new Jewish Messiah, he adopted elements of Catholicism and Islam in his teachings.

Considered by many to be the Nobel prize winner’s masterpiece, it was published in Polish in 2014 and remained a national best-seller for over a year afterwards. By delving into the multi-ethnic world of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the novel raises questions that are highly pertinent in today’s Europe. Although her book sold 170 000 copies in hardcover and was winner of Poland’s biggest literary prize, Tokarczuk attracted harsh criticism. Denounced by nationalists as a traitor, the author received death threats and her publisher had to hire bodyguards for her. “I was very naive. I thought we’d be able to discuss the dark areas in our history,” Tokarczuk admits.

Readers are encouraged to re-examine their own histories as its plot and characters both celebrate and problematize diversity. It speaks to the issues of tolerance and inclusiveness that the current refugee crisis has raised. Particularly in countries like Poland where the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS) has taken a strong stance against the influx of migrants. Indeed the European Commission has just referred a third case to the European Court of Justice on threats to the rule of law introduced by the PiS. Tokarczuk’s 1000 page novel has yet to be translated into English. Publishers in the United States hope to have an English version ready by March 2021. In the meantime it is worth considering the hostile reactions by the ethno-nationalists in Poland. The country’s ruling Law and Justice party are set to triumph in Sunday’s national elections.

An increasingly divided society.

Working from a strong Catholic base, the PiS prides itself on its conservative stance. Party president, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, has stated that PiS exclusively recognises families as ‘one man, one woman and children’. Unsurprisingly, their stance on LBTQ rights is largely intolerant with some local councils in Poland declaring ‘LGBT-free zones’. I recently spoke with human rights activist, Elzbieta Podlesna, who temporarily fled Poland for refuge in Belgium, after her involvement in the so-called ‘rainbow madonna’ incident. This involved appropriation of the iconic Black Madonna with a halo of the LGBT rainbow colours. Podlesna and others believe that Polish society is increasingly divided along conservative/liberal lines. The current government has also used strong rhetoric against the EU’s refugee policies and came under attack for limiting Poland’s refugee quota to just 150, mostly Christian Syrians.

The first codified constitution in modern European history.

Shortly before its demise, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth adopted the first codified constitution in modern European history, the second (after the United States) in modern world history. So advanced was the May 3rd Constitution (1791) in terms of the liberties it provided for its citizens, that its creation caused immediate reaction amongst neighbouring states. Russia, Prussia and Austria all took the opportunity to go ahead with the third and final partition of Poland. So that by 1795, not only the constitution but the state of Poland itself, had ceased to exist. It would be 123 years before Poland would come into existence once more – just in time for the Second World War, followed by decades of Russian communist rule.

Given the turbulent history of this country, it is understandable that nationalism has flourished. It provides the sort of clear, reassuring narrative that has been largely absent from Polish history. Yet, writers like Tokarczuk , provide other less comfortable but far more impressive narratives. Ones that celebrate diversity, dissent and tolerance. In time, Polish politics will hopefully reflect this rich history and in so doing, help to further enrich Europe, as it did 450 years ago.