In a world where virtual reality and fake news are becoming the norm, demand for that highly prized commodity, trust, is rising. In China, the speed of change on a scale hitherto unknown together with a lack of political transparency, has created a large deficit of this vital ingredient. I spoke with researchers from the Leiden Asia Centre on the social credit system, due to be rolled out nationwide this year.

What is the social credit system and how does it work?

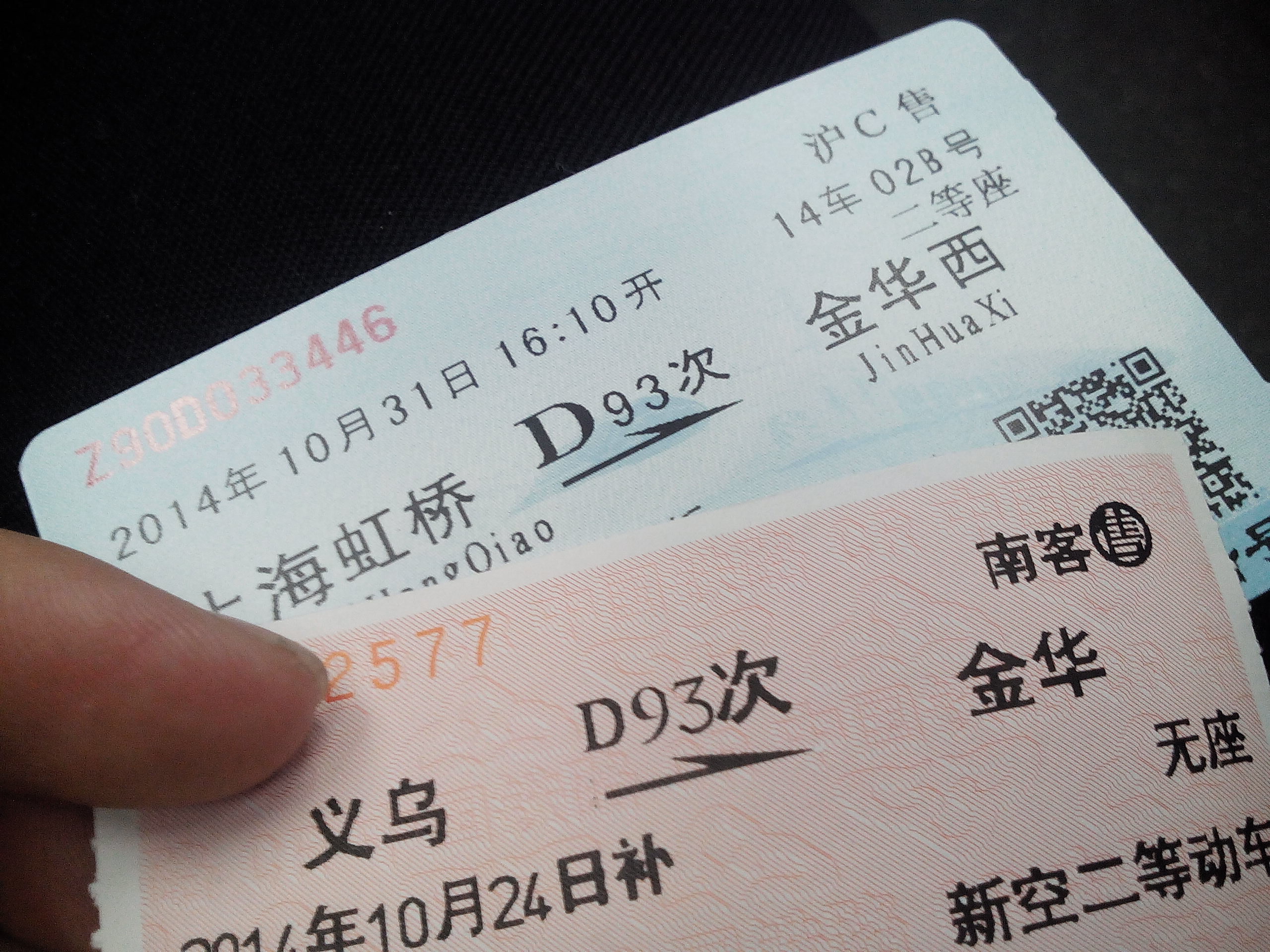

The Chinese government provided the first clear definition of what the social credit system should look like in 2014. According to the system’s founding document, the scheme should “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.” Since then, Dr. Rogier Creemers explains, the government has ‘opened it up to tender’. The result: ‘a huge variety of systems across the country driven by the general principles and spirit of social credit’.

Thus, in 2015 there were 11 pilot schemes but this rapidly grew to 32 and by 2017 there were 623 social credit systems on offer across the country. Thus Associate Professor, Liu Jun, of the University of Copenhagen, points out that currently there is no unified social credit system in China. Some are government led and some are corporate led systems involving companies like Tencent and Alibaba. Liu Jun goes on to draw parallels with Aadhaar in India, the world’s largest biometric database and Germany’s schufa system for credit rating.

However, the Chinese approach, although not yet fully operational, appears to be much more far reaching. PhD candidate, Adam Knight, has spent time in China researching the reality of the social credit system. He explains that the Chinese government has selected 28 model cities from across the country on which others will base their social credit systems.

One that stands out in particular is Rongcheng in Shandong province. It is a relatively small city by Chinese standards, 650 000 people, and represents, ‘a very distilled microcosm of the national system at large’. It is here that Adam Knight conducted his research into the nuts and bolts of the system on the ground. He explains that it is the Credit Management Department’s job to gather information, decide on punishments and rewards and catalog behaviours.

Minus 50 points for spreading rumours on WeChat.

Knight provides an example of the taxi industry. Each taxi driver in Rongcheng is given a social credit ranking. They are pooled in groups of ten with the ‘best’ or most honest taxi driver placed in charge. This person is responsible for reporting misbehaviour from other members of the group. The information is used to create a star rating for each driver which is displayed on the front of the taxi. Other examples include actions like 10 points for clearing snow off the pavement, minus 5 points for arguing with your neighbour or minus 50 points for spreading rumours on WeChat. Drunk driving will probably cause your score to plummet. But donating to a charity or volunteering in one of the city’s programmes will earn you social credit. If your score drops below a certain level you may be banned from receiving government subsidies or attending university.

How is this data being collected? Officials from the department of Credit Management insist that anything that influences your points needs to be backed with official documents. However, Knight explains that there are well over a thousand volunteers in the Rongcheng area whose job it is to ‘snoop on their neighbours’, pen and paper in hand. These social credit records are then passed up on a monthly or sometimes a yearly basis. Cash incentives further muddy the waters of the system and result in data of varying quality. In theory, a person should be given 10 days notification if their social credit score is going to change. But in reality this seldom happens, Knight explains. Inaccurate data undermines one’s ability to appeal against the system.

Social credit system ‘is a tool designed to enhance trust in the market place’ – Dr. Creemers

Chinese media tends to provide what Knight terms, ‘an event driven perspective’ on the introduction of the social credit system. It is presented as life-improving and there is little focus on issues of surveillance or privacy. Chinese law scholar, Dr. Creemers, who argues that China is largely ‘misunderstood’ due to lack of genuine interest from the West, admits that there is ‘no notion of a generalised right of privacy in Chinese law’. Instead, rules on data protection are ‘deeply contextualised’.

Data is not therefore seen as the personal property of citizens and is often collected without their permission. Creemers admits that he doesn’t see any form of GDPR coming to China soon. But describes the social credit system as ‘a tool designed to enhance trust in the market place’. Until recently few Chinese citizens had a bank account. This makes assessing credit worthiness difficult, particularly in a country as large as China. A lot of government held information in China is still on paper. Thus the social credit system is also about digitizing these paper records.

‘China is in a very serious trust crisis’ – Zheng Yefu

But the issue of trust goes deeper than this. “China is in a very serious trust crisis,” said Zheng Yefu, a sociologist at Peking University and author of the book “On Trust.” Reasons for this are varied. Some cite the Cultural Revolution and other political changes that ended traditional societal structures designed to ensure trust. Others say that the demands of a market economy in a society that lacks a well-developed legal and regulatory system is to blame.

The government’s recent morality campaign – ‘Eight virtues and Eight Shames’ is evidence of growing concerns in this regard. But as some commentators point out, the government itself is far from transparent. The release of inaccurate government statistics for political purposes, a general lack of accountability and systemic corruption within the party ranks are hardly the ingredients of which trust is made.

Willing to forego some privacy if it means less fraud and crime.

Ethnographic research by Xinyuan Wang of University College London carried out over a period of 16 months suggests that Chinese citizens view the situation quite differently. Focusing on Shanghai, Wang found that most were willing to forego some privacy if it meant less fraud and crime. Food and drug safety are particular areas of concern. However many also associate the West’s ‘mature credit system’ with high levels of trustworthiness. The rule of law and the trust and transparency that it fosters cannot be replaced by the Communist Party’s social credit system. Perhaps one day Chinese citizens will know this, from first-hand experience.